Build your Model

A financial model can serve multiple purposes, ranging from simple data aggregation to complex forecasting and scenario analysis. Regardless of its complexity, the model should be built for clarity, maintainability, and extensibility. This is where the concept of modular programming, as discussed in Structure your Model, becomes crucial. For examples of this method and inspiration for building your own model, explore projects like the Finance Toolkit, Finance Database, OpenBB Terminal, yfinance, and Riskfolio-Lib.

Regardless of the model’s purpose, applying consistent styling and coding guidelines helps remove the subjective nature of coding. A style guide ensures code consistency, making it easier to read and maintain. This consistency is crucial when multiple developers collaborate on the same codebase or when colleagues transition between teams and need to understand unfamiliar models.

Linters, as discussed in Setting up your Project, automate much of the initial code styling. However, linters cannot enforce choices regarding coding methods, variable naming conventions, or docstring structures. This is where style guides like PEP 8 are essential.

Why a Universal Style is Important

You might be accustomed to specific styling methods from your firm or university. However, adopting universally accepted styles like PEP 8 is highly recommended, as countless developers use them. This standardisation significantly eases collaboration, allowing developers to quickly understand your code. Furthermore, adhering to PEP standards provides clear guidelines and avoids conflicts with automated linters, simplifying the development process.

Default Styling

Throughout this page, PEP (Python Enhancement Proposal) is frequently referenced. A PEP is a technical design document for the Python community, outlining new features, processes, or environmental standards for the language. These proposals represent community consensus, providing established best practices.

The styles described by PEP 8 (see here) define conventions for general code structure. As the default style adopted by numerous developers, it ensures consistency across both internal and external tooling. Reviewing the PEP 8 documentation is recommended for a thorough understanding; this section summarizes the major components.

Key aspects of code layout include:

- Indentation: Use 4 spaces per indentation level. This is the standard in most code editors.

- Maximum line length: While 79 characters is the traditional recommendation (originally based on screen resolution limitations), PEP 8 allows flexibility. Limits up to 99 or even 122 characters are common practice today due to improved screen resolutions.

- Line Breaks: Should generally occur before binary operators, aligning with mathematical conventions where the operator precedes the operand on the new line.

- Blank Lines: Use blank lines appropriately to separate functionality. Surround top-level functions and classes with two blank lines, and methods within a class with one blank line. Use blank lines sparingly within functions to indicate logical sections.

- Source File Encoding: Always use UTF-8 encoding for source files. Code identifiers (variables, functions, classes, comments) should be in English, except for widely understood abbreviations.

- Import statements: Each import should generally be on a separate line. Imports should be explicit, specifying the modules being imported (e.g.,

from package import module1, module2) rather than using wildcard imports (from package import *). Imports should be grouped in the standard order: standard library, related third-party, local application/library specific. - Module Level Dunder Names: Module-level “dunders” (names with double leading and trailing underscores), such as

__version__or__author__, should be placed after the module docstring but before any import statements, except forfrom __future__imports.

Naming Conventions

Recommended naming conventions include:

- Classes: Use

CapWords(also known as PascalCase), likeRatiosorFinancialModel. - Functions: Use

lowercase_with_underscores(snake_case), often starting with a verb, likecalculate_gross_marginorget_data. - Variables: Use

lowercase_with_underscores(snake_case), likemarginorgross_margin. - Constants: Use

UPPERCASE_WITH_UNDERSCORES(SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE), likeINTEREST_RATEorPERIOD. Constants represent values that are not intended to change. - Internal Use (Protected): Use a single leading underscore, like

_income_statement. This convention indicates that a variable or method is intended for internal use within a class or module, although it’s not strictly enforced by Python.

The goal of these conventions is to make code more readable by indicating the intended use of a name (e.g., class, function, variable, constant) simply by its format. For instance, calculate_gross_margin clearly suggests a function, while gross_margin suggests a variable and PERIOD suggests a constant.

Choose descriptive names over overly abbreviated ones. For example, microsoft_trailing_gross_margin is preferable to msft_ttm_gm. While brevity has its place, clarity is paramount, especially considering that code is read far more often than it is written. Avoid generic names like df unless the scope is very limited and the meaning is obvious from context.

When collaborating, remember that your code needs to be understandable by others, even in your absence (e.g., during holidays, sick leave, or after you’ve left the team).

Applying Typing

Use type hints for variables and function signatures as defined in PEP 484 (Type Hints) and PEP 526 (Syntax for Variable Annotations). Type hints improve code clarity and allow static analysis tools to catch potential errors. Examples:

# General definition

revenue: pd.Series = pd.Series([1, 2, 3])

# Multiple possible types based on any

cost_of_goods_sold: pd.Series | float = 5

# Definitions within a dictionary

reported_values: dict[str, float] = {

"revenue": 500,

"cost_of_goods_sold": 200,

"gross_margin": 0.6,

}

# Constant definition (use Final for linters)

from typing import Final

# Multiple possible types based on Pandas

transactions: pd.DataFrame | pd.Series = (

pd.Series([10, 15, 5])

)

# Defining dtypes at the same time

margin: pd.DataFrame = pd.DataFrame(

data=[0.8, 0.3, 0.2],

dtype=np.float64)

Type hints should also be applied to function parameters and return values:

def get_gross_margin(

revenue: pd.Series | int,

cost_of_goods_sold: int) -> pd.Series:

"""Docstring here"""

# Code here

return

def get_cost_of_goods_sold(

transactions: pd.DataFrame | pd.Series,

margin: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""Docstring here"""

# Code here

return

Omitting type hints reduces code clarity, forcing users to rely solely on docstrings or reading the implementation to understand function inputs and outputs.

Writing Docstrings

Write clear and informative docstrings following PEP 257 (Docstring Conventions). Consistent docstring formatting is widely accepted and supported by many development tools. Here’s an example using the Google style format:

def function_name(param1: type, param2: type) -> return_type:

"""

Description of the function and its arguments.

Args:

param1 (type): Description of the first parameter.

param2 (type): Description of the second parameter.

Returns:

return_type: Description of the return value.

Raises:

KeyError: Description of the exception raised.

"""

While this example uses the Google format, other formats like reStructuredText (reST) or NumPy style are also common. The chosen format is less important than ensuring the docstring clearly explains the function’s purpose, arguments (including types), return value(s), and any exceptions raised. The goal is to allow users to understand the function without needing to inspect its source code.

Aim for comprehensive docstrings; it’s generally better to provide too much detail than too little. Docstrings are an excellent place to explain underlying financial theory or complex logic within the function. Below is an extensive example (from the Finance Toolkit) demonstrating the level of detail possible:

def get_capital_asset_pricing_model(

risk_free_rate: pd.Series | float,

beta: pd.Series | pd.DataFrame | float,

benchmark_returns: pd.Series | float,

) -> pd.Series | pd.DataFrame | float:

"""

CAPM, or the Capital Asset Pricing Model, is a financial model used to estimate

the expected return on an investment, such as a stock or portfolio of stocks. It

provides a framework for evaluating the risk and return trade-off of an asset or

portfolio in relation to the overall market. CAPM is based on the following

key components:

1. Risk-Free Rate (Rf): This is the theoretical return an investor could earn from

an investment with no risk of financial loss. It is typically based on the yield

of a government bond.

2. Market Risk Premium (Rm - Rf): This represents the additional return that

investors expect to earn for taking on the risk of investing in the overall market

as opposed to a risk-free asset. It is calculated as the difference between the

expected return of the market (Rm) and the risk-free rate (Rf).

3. Beta (β): Beta is a measure of an asset's or portfolio's sensitivity to market

movements. It quantifies how much an asset's returns are expected to move in relation

to changes in the overall market. A beta of 1 indicates that the asset moves in

line with the market, while a beta greater than 1 suggests higher volatility, and

a beta less than 1 indicates lower volatility.

The formula is as follows:

Expected Return (ER) = Risk-Free Rate (Rf) + Beta (β) * Market Risk Premium (Rm - Rf)

Args:

risk_free_rate (pd.Series | float): the risk free rate.

beta (pd.Series | pd.DataFrame | float): the beta.

benchmark_returns (pd.Series | float): the benchmark returns.

Returns:

pd.Series | pd.DataFrame | float: the capital asset pricing model.

Raises:

TypeError: if beta is not a pd.Series, pd.DataFrame or float.

"""

if isinstance(beta, pd.DataFrame):

capital_asset_pricing_model = pd.DataFrame(

columns=beta.columns, dtype=np.float64

)

for column in capital_asset_pricing_model.columns:

capital_asset_pricing_model.loc[:, column] = risk_free_rate + beta[

column

] * (benchmark_returns - risk_free_rate)

elif isinstance(beta, (pd.Series | float)):

capital_asset_pricing_model = risk_free_rate + beta * (

benchmark_returns - risk_free_rate

)

else:

raise TypeError(

"beta should be a pd.Series, pd.DataFrame or float, "

f"not {type(beta)}"

)

return capital_asset_pricing_model

Creating Documentation

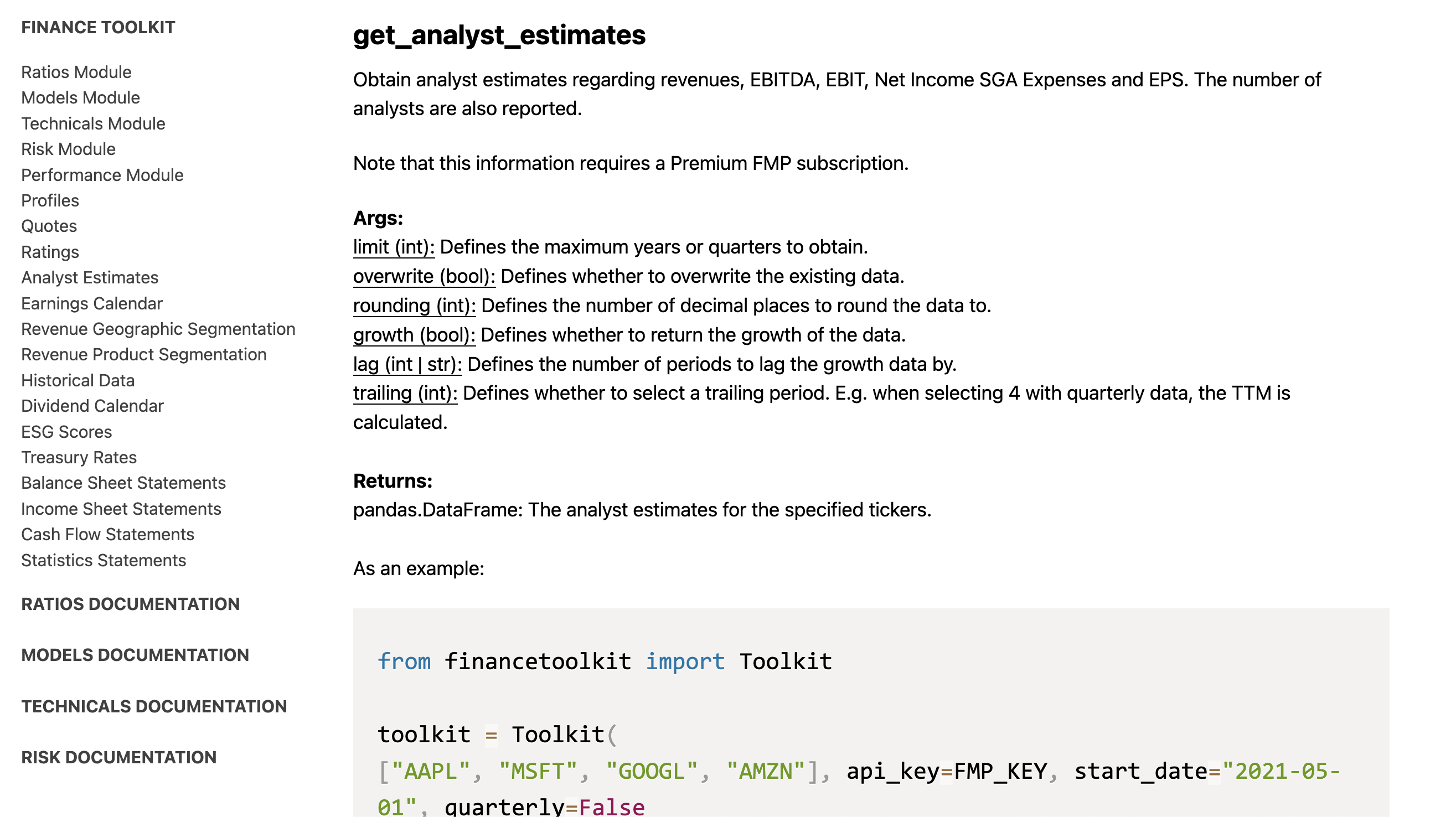

Besides styling and docstrings, documentation is actually pretty important if you want to share your code with others. This is where Sphinx comes in. Sphinx is a tool that makes it easy to create intelligent and beautiful documentation for Python projects (or other documents consisting of multiple reStructuredText or Markdown files).

Other popular documentation generators include MkDocs. Additionally, platforms like Read the Docs can host documentation generated by these tools. The Finance Toolkit documentation serves as an example, showcasing a polished result achievable with such tools (though this specific example uses custom elements alongside standard tooling).

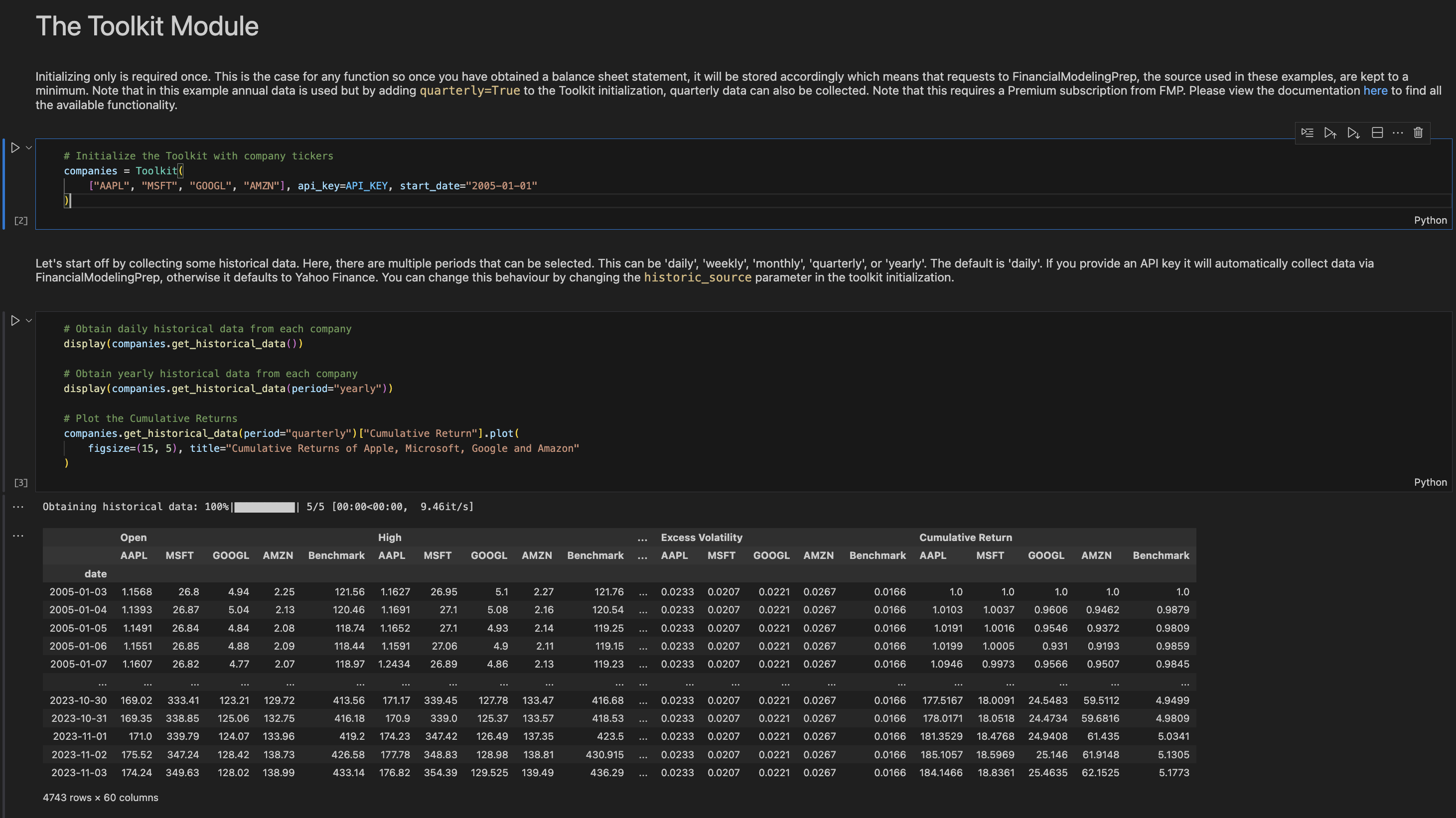

Effective documentation goes beyond API references (descriptions of individual functions). It should include tutorials, conceptual explanations, and practical examples, often using Jupyter Notebooks to demonstrate use cases. These examples help users understand the model’s logic and applications. Store such examples in a dedicated examples directory, as suggested in Structure your Model. See a snippet from the Finance Toolkit’s Getting Started Notebook below:

In corporate environments, internal wikis (like those in Azure DevOps or Confluence) are valuable for sharing higher-level project information, architectural decisions, and team processes, often using Markdown and benefiting from version control.

Well-written docstrings allow the main documentation to focus on the model’s overall structure, usage patterns, and concepts, rather than repeating low-level function details. This approach is particularly helpful when the model serves as a back-end, enabling non-programmers (like Financial Analysts or Portfolio Managers) to understand its capabilities and assumptions, bridging the gap between technical and domain experts.

After establishing these coding and documentation practices, the next crucial step is testing. Proceed to Test your Model to learn more.